|

Despite its setbacks, the story of Biosphere 2 can get us thinking about the importance of wonder again. "Biosphere 2 is the world's largest controlled environment dedicated to understanding the impacts of climate change. Our researchers have created the unique biomes to help answer the most complex questions of today and tomorrow about sustainability, conservation, and humanity's impact on Biosphere 1 – our own Earth."

-University of Arizona Research Team In the early 1990s, a group of dreamer scientists embarked on an ambitious project that would push the boundaries of scientific exploration and innovation. Biosphere 2, a massive enclosed ecosystem spanning over three acres, was designed to mimic Earth's biosphere and serve as a self-sustained environment for human habitation. The ultimate goal of this groundbreaking experiment was to explore the possibility of creating self-sufficient habitats for future space exploration on Mars or the moon. "Designing an artificial ecosystem that captures the essential essence of the original biosphere on Earth was much like playing Noah, choosing which organisms could be assembled into a stable, self-sustaining network and then bottled in an enclosed environment." -Jane Poynter The Biosphere 2 experiment was a testament to the power of human ingenuity and the relentless pursuit of knowledge. The scientists involved in the project dreamed of creating a miniature version of Earth, complete with diverse ecosystems, including rainforests, deserts, and even an ocean. By studying the intricate interactions between these ecosystems and the human inhabitants, they hoped to gain valuable insights into the complex web of life that sustains our planet. It's clear that the experiment holds important relevance to today's world of scientific exploration and innovation. The successes and failures of the project provide a wealth of knowledge that can guide future endeavours in space exploration and sustainable living. Some of the innovations that worked well during the experiment include the use of advanced recycling systems, efficient food production techniques, and the cultivation of diverse plants. Despite the Biosphere 2 experiment's setbacks, such as fluctuating oxygen levels and challenges in maintaining a balanced ecosystem, these obstacles provided excellent opportunities to learn about the challenges of surviving in a closed system. The scientists involved in the project demonstrated remarkable resilience and a growth mindset, adapting to the challenges and finding innovative solutions under tight budgets and short timelines. A lesson that all students, regardless of age, can benefit from. One of the most significant hurdles during the experiment was the unexpected drop in oxygen levels. Initially designed as a completely sealed environment, Biosphere 2 began experiencing dangerously low oxygen levels. This was due to several unforeseen factors, such as the concrete structure absorbing oxygen and the overgrowth of soil microbes consuming oxygen and releasing carbon dioxide. Engineers injected supplemental oxygen into the facility, a controversial move because it compromised the integrity of the closed system but was crucial for the safety of the inhabitants. Additionally, they addressed the problem of oxygen absorption by sealing the concrete surfaces within the facility, and reacting with the air to reduce oxygen levels. Finally, the facility's microbiome adjustments were made to improve the carbon dioxide-to-oxygen ratio. Many in the public mocked this move as a giant failure, showing that Biosphere 2 was unsustainable. Considering the scope and scale of the project, many scientists felt that this was an unforeseen issue and actually provided interesting insight into managing a complex system for future missions. The failure was a powerful lesson for aspiring scientists and innovators, reminding them that setbacks are an integral part of the scientific process and that success often lies in the ability to learn from failures and keep pushing forward. Looking towards the future, the potential applications of artificial intelligence in biosphere initiatives and space colonization are immense. AI-powered systems could assist in monitoring and regulating the complex ecosystems within enclosed habitats, optimizing resource management, and even predicting potential issues before they arise. Moreover, AI could play a crucial role in helping humans survive and thrive on Mars or other planets, by analyzing data, providing decision support, and facilitating communication with Earth-based teams. The Biosphere 2 experiment not only advanced scientific understanding but also captured the imagination of the general public. It sparked a renewed interest in understanding our Earth, the importance of preserving its delicate ecosystems, and the possibilities of exploring other planets. In the spirit of Carl Sagan's Cosmos, which popularized the universe for the masses, Biosphere 2 brought the wonders of science and the potential for human exploration to the forefront of public consciousness. As Carl Sagan famously said, "*Somewhere, something incredible is waiting to be known.*" This quote encapsulates the essence of scientific exploration and the boundless potential for discovery. Biosphere 2 embodies this spirit of curiosity and the drive to push the limits of human knowledge. It serves as a reminder that humans are naturally ambitious and innovative. Many of the great discoveries and innovations that benefit us today are the result of dreamy scientists whose ideas were often dismissed outright. For educators, the Biosphere 2 experiment provides a rich source of inspiration for fostering an innovation mindset in students. By incorporating hands-on, inquiry-based learning approaches, such as design thinking, genius hour and innovation fairs, teachers can encourage students to think creatively, solve problems, and embrace the challenges that come with scientific exploration. By exposing students to the stories of the Biosphere 2 scientists and their achievements, educators can ignite a passion for science and inspire the next generation of innovators. Reflecting on the legacy of Biosphere 2, it is clear that its impact extends far beyond the scientific community. It stands as a symbol of human ingenuity, resilience, and the boundless potential for exploration and discovery. By drawing inspiration from this remarkable experiment, we can cultivate a culture of innovation and encourage future generations to dream big, take risks, and push the boundaries of what is possible. The Biosphere 2 experiment serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of scientific exploration and the potential for human innovation. As we face the challenges of the future, from climate change to space exploration, it is important to remember the lessons learned from Biosphere 2 and foster an innovation mindset in the next generation of scientists and problem-solvers. Together, we can unlock the incredible possibilities that await us and make the dreams of yesterday the realities of tomorrow. Last week, the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) conference was held in Denver, Colorado. For those in the ed-tech world, ISTE is the Kentucky Derby of conferences. If you're looking for classroom technology, you'll find it here – from tech giants like Microsoft to niche players like Quizizz.

This year's hot topic? You guessed it – Artificial Intelligence, or as some jokingly call it, Skynet... Keynote speakers like Sinead Bovell discussed AI's impact on the workforce and education, while self-proclaimed "#changeagent" teachers signed books about AI in the classroom. Nearly every ed-tech company now boasts AI features, promising to generate rubrics, presentations, tests, and even parent emails at the click of a button. By a large margin, the most alarming development is software that can generate a rubric, upload it to AI, and then grade students' work. What's more concerning? The application or the unbridled excitement of teachers discovering this "superpower." Admittedly, conferences like ISTE, regardless of industry, often serve up more fluff than substance. Most teachers in North America have never heard of ISTE and have little interest in AI. Why? Because many schools are still struggling with outdated technology. It's possible that AI might follow the path of the Internet – a fantastic tool that hasn't fundamentally changed day-to-day classroom activities. This disconnect is what frustrates me most about education today. Scroll through the social media bios of ISTE attendees, and you'll find an endless parade of self-promotion. "Change makers," "AI experts," "inclusive leaders" – the list of trendy tags goes on. While these posters represent a small percentage of attendees, many are presenters or organizational representatives. They're the ones steering the conference and, by extension, shaping the narrative around education technology. So, why should we care? The danger lies in the growing gap between these self-promoting "Instagram educators" and the daily realities of schools across North America. Teaching, at its core, is the most artistic of blue-collar jobs. It requires intuition, a sense of "mana," as surfers might say. Each student arrives shaped intensely by their last 24 hours, and it takes a skilled educator to motivate and teach them effectively. Yet, teachers must also navigate government-mandated curricula and assessments, regardless of classroom dynamics. AI proponents aim to streamline this process. "Look how easy it is to design a worksheet!" they boast. "Now you can spend more time with your students!" It sounds enticing, especially for educators seeking efficiency. But as readers of this website know, we must always ask ourselves: What is the true purpose of education? The sobering reality is that 21st-century education resembles the art world more than the process-driven industrial model that AI experts insist on improving. Like art, education varies wildly across geographic and demographic lines. Some teach through a post-modern lens, others take a classical approach, and many develop their own unique style. Schools and districts approach learning differently too. From a bird's-eye view, it looks like we're throwing spaghetti at the wall and burning through funds in the process. Research on effective teaching methods is limited and often biased (remember the multiple learning styles fiasco?). Education schools lack science-backed methodologies and face criticism for being overly political. We send new teachers into the world with a "good luck" and then wonder why they lean on activism. This brings us to the crux of the issue: With so many inconsistencies in education, how can anyone claim to be an expert in AI's classroom applications? The self-aggrandizing educators who promote their expertise have been given too much leeway, and we're following marketing strategies rather than wisdom. We're witnessing the loss of generational teaching experience in real-time, leaving the industry without a post-mortem on their insights. They're old dinosaurs who can't survive in the new world, we say. We assume technology will fix our current problems, a notion that even forward-thinking Carl Sagan warned against: "We've arranged a society based on science and technology, in which nobody understands anything about science and technology." Perhaps we should heed Sagan's warning and remember that when it comes to technology in education, we have no idea what we're doing. It might be more effective to turn away from self-promotion, put the hard hat back on and focus on creating critical-thinking, life-long learners. It's not sexy, but it works. After reading Jonathan Haidt's latest book, The Anxious Generation, I was left wondering: Is it really this bad?

Having worked as an educator with elementary-aged students (K-8) for over 15 years, I paid close attention to Haidt's data, especially for ages 10-14. Throughout the book, I juxtaposed my experience with his findings to make sense of my day-to-day experiences as a middle school teacher. Often, data-driven books like *The Anxious Generation* highlight trends across demographics but fail to capture the nuances of daily life in the classroom. This is understandable; no author can account for every variable when proposing a hypothesis. Instead, we rely on large data sets to determine trends. The trends presented in the book are indeed disheartening. Teens and pre-teens, both male and female, are experiencing a mental health crisis. Haidt connects this trend to the rise of the social media generation, who now spend the majority of their lives on a device. So, what does this look like on the ground from a teacher's perspective? I've often suggested that the pandemic was a significant factor in the decline of Gen Z's mental and physical health. The uncertainty around the role of school in the early days of the pandemic created a chaotic environment, prompting questions with no clear answers. I remember pondering: What are the minimum requirements for online learning? Should it be asynchronous or synchronous? Should students be required to participate in some capacity? Do they need to have their cameras on? Should they be graded? Amid the chaos, norms for online learning were formed across Canada and the US. Younger students were taught synchronously in a traditional style, while older kids had opportunities to work asynchronously. There were problems with both, but we hoped that throwing enough spaghetti at the wall would at least stave off some of the learning loss. As expected, students with attentive parents, access to resources, and a reasonable sense of self-discipline soared above those missing one or more of these variables. Many students suffered alone, inevitably leading to an increase in anxiety and depression, much of which still affects them today. However, something happened during the pandemic that many educational leaders missed: Students learned that school was optional. The middle school students I taught during the pandemic checked out when forced to learn online. In some cases, I never heard from them at all, nor did they respond to emails. They never got punished for this. When deadlines came and went, I was not allowed to fail students. At the time, it seemed the right thing to do. However, as more assignment cycles passed without submissions, it started to stick. Students realized that school was optional. When things returned to normal, the vibe of school changed. Students seemed less motivated to participate in school and definitely less intrinsically motivated overall. It's hard to pin down the exact vibe, but it seemed that the wind had been taken out of their sails. It was almost as if they didn't know why they needed to be in school other than their parents making them. Along with the wave of indifference came a tsunami of identity crises that shook the foundations of school cohesion. Middle school students began identifying themselves in the third person, using they/them pronouns. Some went further to identify as the opposite sex. It wasn't just one or two; it was more than half in some classes. Just a mere two months prior, they had been wonderful, loving students with little support required. Now, they all seemed to have issues—anxiety, depression, ADHD—and were happy to tell you about it and even more excited to use it as a way to avoid actual school work. In times of rapid, drastic change, real leaders emerge. Unfortunately, in many cases, including mine, leadership embraced this new world with little critical thought about the long-term consequences. Students were allowed to hide their identities from their parents, meaning they could show up at school and change their name and gender, and teachers were not allowed to mention it outside the school walls. Students would come to school with what appeared to be cuts on their arms, and all I could do was hand the case to the leadership. The trap that school leadership fell into was directly connected to one of the great untruths from The Coddling of the American Mind: "Always trust your feelings." As Haidt and Lukianoff explain, ideas like "personal truth" and "lived experience" too often place feelings on the same level as facts. Feelings, of course, are subject to countless cognitive biases. Facts are facts because they're exempt from feeling. When we let young people, who are in the midst of puberty's emotional rollercoaster, believe their feelings are the truth, we end up with students identifying as different names and pronouns at school. A leadership team that supports this untruth creates a negative feedback loop where anything goes at any time because students feel like it should. As Katharine Birbalsingh suggests, students need tight guardrails because the world is a big, unknown place. Having boundaries allows them to explore within those boundaries while mitigating danger. This doesn't mean smothering them with rules; it means enforcing the rules to provide the 'safety' that students seek. Educators have let students' feelings drive their learning, resulting in a curriculum focused on student motivations rather than school goals. A great example is the reduction in the rigor of mathematical education. In California schools, algebra has been removed from the 8th-grade curriculum. In Ontario, 9th grade has become de-streamed (meaning no advanced classes). The goal wasn't to punish the smart but to help motivate the bottom-of-the-curve students who may "hit their stride" as they mature. It was thought that difficult math would turn students off the curriculum before they matured enough to "really get it." Unfortunately, there is no statistical evidence supporting this assumption. Jo Boaler, the Stanford math educator who led this charge, has recently come under fire for manipulating data on this very issue. Another important variable is social media. The Anxious Generation beautifully describes the overt effects of social media on kids' mental health, so I won't delve deeply into it. (As I write this, my 10-year-old is endlessly scrolling YouTube shorts on his tech time. More about this in another post.) However, there are downstream effects that the book doesn't explore enough. One significant change I've noticed over the years is groupthink. While the book mentions the susceptibility of females to groupthink, it is a larger issue than we imagine. Many middle school students will be captured by groupthink in an attempt to fit in. It has become increasingly ideological over the years. Pronoun usage is the most obvious example. Often, those students who use different pronouns do so as a cluster of friends rather than being the only one in a friend group to do so. In my experience, it's the students traditionally labeled as part of the outgroup. This makes intuitive sense—one way to differentiate yourself is to change your identity entirely. The speed and intensity of this change is directly influenced by social media. From my experience, there is a direct correlation between the amount of time someone spends online and the degree to which they echo a specific doctrine. Students who spend time on platforms like TikTok are driven by algorithms into feeds where their ideas are easily validated without criticism or critical thought. When these ideas are brought into school, teachers are forced to either validate, ignore, or push back. In our current educational environment, validation seems to be the only viable pathway. Ignoring is something I've practiced with the intention of protecting my job. Pushing back is the ultimate no-no and, in the one time I tried, landed me in a meeting with the head of the school. What can educators do to ensure students have an environment that both challenges their learning and makes them feel secure? One idea is to remove the focus on lived experience and instead focus on innovation. By innovation, I mean inspiring students to create concrete solutions to issues. For example, take history as it is, and instead of trying to rewrite it, have students focus on the innovations that made the world the place it is today. Slavery, or in Canada's case, the treatment of Indigenous people, is a hot topic in education. When teaching these issues, the focus is almost entirely on the disadvantages of the legacy of these systems. Teaching students that the legacy of the system is inherent today and is essentially stuck unless we make drastic 'equity' changes is not an effective means to change that system. Certainly, teaching the dark side of history shouldn't be ignored in education. However, it would be much more beneficial to students to show how changes were made to improve the lives of disadvantaged people. Britain outlawed the slave trade and used its powerful navy to enforce the rule against other sovereign nations. Without this action, slavery would have taken much longer to dissolve. In Canada, students should be taught the policies that were put in place to help support the Indigenous people to thrive. These include tax benefits, grants, and other government programs implemented federally to correct some of the misgivings. The students can then examine the success rate of these programs and develop strategies to continue to integrate marginalized individuals into society. The trouble with only showing the dark side of history is that it inevitably leads to activism in the form of protest. When students are taught that everything is systemic and cannot be changed, it often results in very binary thinking. Sure, this can be effective in some cases. However, it is such a common tactic now that its effectiveness has been greatly eroded. Blocking traffic in the name of climate action ends up losing public support, not gaining it. Teachers who promote this methodology would argue that 'awareness' of the issue is the ultimate goal. Unfortunately, the internet age has created an environment where we have theme days, weeks, months, and even *seasons* for all kinds of issues. We've over-saturated the attention market. But is it really that bad? The culture inside educational institutions has changed enough that it is increasingly difficult to challenge ideas constructively. The trouble I have experienced is related to the degree and intensity to which ideas and concepts are implemented. For example, our school raises the pride flag at the beginning of Pride Month in a school-wide ceremony. I objected to having students from K-6 attend this ceremony, citing that it is largely irrelevant to their stage of development and may cause confusion, especially if some of these issues haven't been discussed at home. The blowback I received from what I thought was a reasonable question was intense. The organizers of the event couldn't fathom why I would question anything about it and felt personally offended that I offered such a suggestion. This is the difference between five years ago and today. People are so entrenched in their beliefs that it is almost impossible to have a difficult conversation. The result is that these ideas do end up going too far. In one heinous example, a grade 9 student stood up at a school-wide ceremony during a sombre assembly reflecting on the Montreal Massacre and said she was scared to leave the house because white men were going to rape her. Instead of being reprimanded, she was celebrated as brave. The slippery slide into aggressive activism happens when we don't put up appropriate guardrails for students. Educators have created an environment where students' thoughts and feelings are paramount in the classroom. It is believed that unless kids feel safe, they will not learn. This would certainly be appropriate for the pre-internet generation, but in today's student body, who are chronically online, it doesn't work because they end up bringing their polarizing beliefs into the classroom without any challenge from the adults in the room. Educational leaders need to decide what exactly the purpose of school should be. What should the students look like when they graduate? What are the non-negotiable skills they should have? How will you know they have those skills? Once these questions are answered, you can work backward to find the classes, programs, and extracurriculars needed to produce high-functioning students who are prepared to enter the next phase of their educational or life journey. When you use this lens to view the purpose of education, you quickly realize that safetyism, pronoun usage, and critical social justice are not key initiatives for producing flourishing students. Educators often need reminding that we are not substitute parents and certainly don't hold the moral high ground over them. "Security is mostly a superstition. It does not exist in nature, nor do the children of men as a whole experience it. Avoiding danger is no safer in the long run than outright exposure. Life is either a daring adventure, or nothing."

- Helen Keller In her book The Open Door, Helen Keller argues that security is mostly an illusion. These words resonate deeply in today's educational landscape. As schools increasingly promote the concept of safe spaces, trigger warnings, and microaggressions, it is of utmost importance to urgently question whether these measures effectively protect students or merely postpone their exposure to potentially threatening or disagreeable ideas and concepts. In their influential work, "The Coddling of the American Mind," Jonathan Haidt, a social psychologist, and Greg Lukianoff, a constitutional lawyer, present compelling evidence that despite the growing prevalence of safe spaces and related practices, mental health diagnoses among students have been sharply on the rise. This raises concerns about the efficacy of these protective measures and suggests that a different approach may be necessary. Haidt believes that an increase in safetyism during early childhood development has led to a lack of exposure to conflict and uncomfortable situations, resulting in a fragile mindset during adolescence. Students who are unequipped to handle difficult situations and are exposed to conflicting ideas end up demanding safe spaces and trigger warnings. Often, educators forget that it was the students who originally demanded protection in schools, not the other way around. To combat the culture of safety in schools, educators should consider embracing the concept of anti-fragility, as described by Nassim Taleb in his book 'Antifragile.' Taleb argues that exposure to adversity can lead to significant positive benefits, much like how our immune system function improves through exposure to different viruses. By encountering and overcoming challenges, individuals can develop greater resilience and adaptability, especially over the long-term, offering a promising future for our educational system. In education, fostering anti-fragility would involve exposing students to a diverse range of ideas, even those that may be uncomfortable or disagreeable. This exposure can help students develop critical thinking skills, empathy, and the ability to engage in constructive dialogue with those who hold different viewpoints. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) offers a valuable framework for managing fears, phobias, and ideas that students may disagree with. CBT emphasizes the importance of confronting and reframing negative thoughts and beliefs, rather than avoiding them. By incorporating CBT principles into educational practices, students can learn to manage their emotional responses to challenging situations and develop greater psychological resilience. To set an anti-fragility mindset in schools, educators can implement several strategies: 1. Encourage open and respectful dialogue: Create a classroom environment that promotes the exchange of diverse perspectives and encourages students to engage with ideas they may find challenging or uncomfortable. 2. Teach critical thinking skills: Equip students with the tools to analyze arguments, evaluate evidence, and form their own well-reasoned opinions. 3. Provide opportunities for controlled exposure: Gradually introduce students to increasingly complex and challenging ideas, allowing them to build resilience and adaptability over time. 4. Model anti-fragility: Educators should demonstrate their own willingness to engage with challenging ideas and model the behaviours they wish to see in their students. By embracing anti-fragility, teachers can help students develop the skills and mindset necessary to thrive in an increasingly complex and diverse world. Rather than shielding students from adversity, we should equip them with the tools to navigate and grow from challenging experiences. The potential long-term benefits of fostering anti-fragility in students are significant. Resilient and adaptable individuals are better prepared to face the challenges of personal and professional life, from navigating difficult relationships to overcoming setbacks in their careers. By learning to engage with discomfort and uncertainty, students can develop a growth mindset that will serve them well throughout their lives. While the intention behind safe spaces and related practices may be noble, it is essential to recognize that safety is largely an illusion. By embracing the concept of anti-fragility and providing students with the tools to manage their exposure to challenging ideas and situations, educators can help create a generation of robust, thriving individuals who are prepared to face the complexities of the world head-on. Helen Keller had every right to demand a safer environment, yet she chose to take a difficult but more fulfilling path. In a modern world filled with endless abundance, we have forgotten to nurture the adventurous spirit of youth. Without it, life is nothing. Challenge-based learning (CBL) is a powerful tool that enables students to tackle personal, local, or global challenges while gaining knowledge across various subjects like literacy, math, science, technology, and the arts. Its core aim is to motivate students by connecting their learning to real-world problems, making their educational journey more meaningful and impactful.

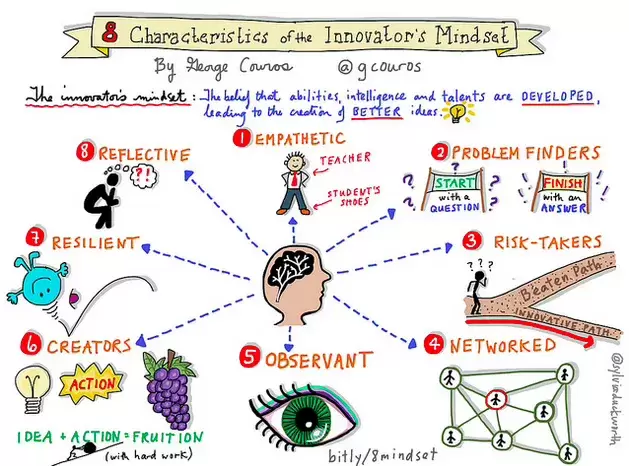

One of the fantastic aspects of CBL is its flexibility. Unlike other learning models such as project-based learning, CBL can be implemented in classrooms of any size and duration. Whether you have just a single lesson or an entire school year, CBL can be tailored to fit your needs. The ultimate goal is to help students apply their learning to develop essential job and life skills, empowering them to tackle even larger challenges in the future. CBL can be seamlessly integrated into almost any subject at any time. Let's explore its key phases: Engage, Investigate, and Act. Engage Big Ideas: These encompass topics that are significant to your class, community, or the world at large. For instance, themes like Climate Change, Social Media Impact, the Purpose of Education, Democracy, or Artificial Intelligence can serve as starting points. The goal here isn't to pinpoint a specific problem but to brainstorm overarching ideas that encapsulate numerous smaller concepts. This approach helps students understand the complexity of challenges and encourages them to think critically. For example, when exploring Climate Change, students can delve into subtopics like global warming, deforestation, or plastic pollution in oceans. Embracing big ideas fosters diverse perspectives, allowing room for exploration without the fear of a wrong answer. Essential Question: This narrows down the focus to a specific area that students can explore. Essential questions are framed to be reasonable, achievable, and realistic, often starting with "how" or "how might we." For instance, in the context of Climate Change, an essential question could be: "How can we reduce the amount of Carbon Dioxide in the air?" or "How might we minimize our school's carbon footprint?" It's crucial for essential questions to be open-ended, avoiding single-solution scenarios, which could indicate a narrow scope. Challenge: This connects the big idea and the essential question, serving as the driving force behind the learning process. Challenges should be broad and extend beyond individual or team boundaries. For example, if the essential question revolves around reducing the school's carbon footprint, the challenge could be "To promote a healthy environment." Depending on the context, students may opt for a more localized challenge, such as "To construct an environmentally friendly school." Investigate Guiding Questions: Once a challenge is identified, students embark on a journey of exploration. The cornerstone of this phase is questioning, as it lays the groundwork for further investigation. Educators play a vital role in guiding students to formulate insightful questions. Depending on students' age and skill level, teachers may scaffold questions or provide examples to enhance students' questioning skills. Using the essential question as a compass, students delve deeper into the issue, posing inquiries that drive their research. For instance, when addressing the question "How might we build an environmentally friendly school?" students might ask: "What defines an environmentally friendly school?" or "What steps can we take to improve our current environmental practices?" To facilitate this process, educators can employ various techniques, such as timed tasks where students generate questions independently and then collaborate to refine them. Additionally, leveraging shared documents like Google Slides or Jamboard allows for community or expert input, enriching the question generation process. Activities and Resources: This stage involves creating a roadmap for addressing essential questions. Students brainstorm tasks and activities aimed at answering these questions. For instance, when exploring the concept of an environmentally friendly school, activities could include researching existing eco-friendly schools, identifying accreditation bodies, or reaching out to relevant organizations for insights. Educators may need to provide additional support, especially for younger students, in aligning tasks with essential questions. However, as students progress, they gain independence in navigating research avenues. Synthesis: Here, students consolidate their research findings into a cohesive narrative. Visual tools like infographics or spreadsheets aid in presenting information effectively. This phase not only facilitates knowledge synthesis but also serves as the foundation for the final phase—Act. Act Solution: Armed with comprehensive research, students design innovative solutions to address the challenge at hand. It's essential to emphasize the importance of creating solutions that are novel, feasible, and impactful. While encouraging creativity, educators should steer students away from overly simplistic solutions and encourage deeper exploration. For instance, instead of a conventional poster campaign to reduce waste, students could design a pedal-powered generator to illustrate energy consumption. This approach integrates additional skills like design and engineering, enriching the learning experience. Implementation: Once solutions are finalized, students transition to implementing their ideas within the community. Whether it's showcasing their projects at school events or soliciting feedback from community members, this phase emphasizes real-world application. Research indicates that students who teach others about their projects retain information better, highlighting the importance of effective communication and dissemination of solutions. Evaluation: The final step involves reflecting on the entire process. Students assess their journey, identifying areas for improvement and celebrating successes. Reflection can take various forms, including written journals, feedback forms, or video reflections. Additionally, articulating the CBL process reinforces learning, ensuring students internalize the value of each phase. The bottom line Challenge-Based Learning equips students with the skills and mindset needed to tackle complex real-world challenges. By fostering inquiry, innovation, and collaboration, CBL transcends traditional learning boundaries, empowering students to become active agents of change. Let's embrace the power of CBL in our classrooms and nurture the next generation of problem solvers and innovators! In his book The Innovator's Mindset, George Couros emphasizes the importance of embracing change, taking risks, and nurturing creativity in students and educators. He encourages a shift away from simply complying with rules and norms and toward fostering curiosity, exploration, and adaptability.

However, translating these ideas into classroom practice can be challenging, especially for educators without business experience. Innovation can mean different things, even within the business community, let alone in education. Without relevant experience, educators may struggle to create or recognize an innovative environment. So, what does an innovative classroom look like? This series of posts aims to help educators - whether experienced or not - begin to cultivate a culture of innovation in their classrooms. It's essential to remember that Couros' innovator's mindset is a guiding principle rather than a strict blueprint. Implementing such an environment in a class with up to 40 students and limited resources over a year is undeniably tricky. Moreover, data consistently shows that traditional methods like rote learning in subjects such as math and language still yield effective results. Hence, discarding traditional approaches entirely in favour of innovation may be premature. Nevertheless, there are opportunities to encourage students' critical thinking and questioning by strategically integrating projects that align with Couros' principles of innovation. It's important to note that while 10-year-olds may possess remarkable creativity, their ability to apply innovation strategies consistently may be limited due to their frontal lobe development and lack of life experience. This doesn't mean they can't innovate; instead, we should adjust our expectations accordingly. Now, let's discuss how educators can foster an innovative mindset among their students. Challenge-Based Learning (CBL) is an approach that engages students in solving real-world problems. Teachers present a broad issue or question, and students generate their own questions to explore the topic. This method, which spans various subjects, allows students to personalize their learning experiences and fosters intrinsic motivation. For example, in a science unit on space, students could explore the future of humanity in interplanetary travel. They might investigate the possibility of life on other planets or the challenges of establishing a human colony on Mars. Students develop critical thinking skills through independent and group inquiry while addressing complex issues. Genius Hour, inspired by Google's practice, allows students to explore topics of personal interest. While providing students with freedom, teachers offer guidance to ensure meaningful learning experiences. This structured approach encourages students to explore their passions and develop skills like problem-solving and self-direction. Makerspace and Minecraft Fridays provide opportunities for hands-on, creative exploration. Teachers can allocate time during the week for students to work on innovative projects or set aside dedicated sessions, like Friday afternoons, for collaborative problem-solving activities. These initiatives not only foster creativity but also encourage teamwork and resilience. Minecraft Education, a popular game among students, offers a sandbox environment for creative expression and problem-solving. By integrating Minecraft into the curriculum, teachers can leverage students' interests to promote innovative learning experiences. While these strategies are not new, they remain effective in cultivating an innovative culture in the classroom. The goal is not to produce the next Space X rocket but to equip students with the skills and mindset to navigate an ever-changing world. By embracing innovation, we empower students to dream big and overcome challenges, preparing them for the uncertainties of the future. After World War II, something incredible happened. Military factories in the US and Canada, once churning out weapons of war, shifted gears to produce consumer goods like toasters and cars. They needed workers to fill the demand. The soldiers returning from WW2 needed jobs, and this kickstarted a golden era for the middle class. Picture this: families with decent paychecks buying homes and cars and snapping up all sorts of cool gadgets like TVs.

However, there was a catch. The whole supply-and-demand dance of economics didn't always play nice. Companies, driven by the free-market hustle, got obsessed with efficiency. So, they went hunting for ways to trim costs, boost innovation, and go big. And you know what that meant? Shipping jobs overseas where labor was cheaper. Sure, it saved them a bundle, but quality sometimes took a nosedive. Fast forward to today, and we're still squabbling about the pros and cons of globalization. But let's face it: most of the stuff we buy isn't stamped "Made in the USA" or "Proudly Canadian." Think about your phone or computer—chances are, they're born far from home. Even big shots like Apple and Microsoft just slap their labels on, leaving the manufacturing to others. And that's leaving out the engineering brainpower that's jetted off to places like China. Modern economics is like trying to solve a riddle inside a mystery. Money flies around like confetti, bouncing between investments and newfangled things like cryptocurrencies. It's a rollercoaster ride where predicting the next twist is anybody's guess. Now, what's the deal for education in all of this? Gone are the days when teachers could pat themselves on the back, knowing they were prepping students for a secure future. Careers in finance, tech, and marketing are shape-shifting faster than you can say "job security." Thanks to inventions like A.I., the job market is a wild, unpredictable beast. You might graduate top of your class in accounting, but there's no guarantee you'll snag that dream job anymore. So, what's the game plan for educators? It's time to update the old playbook and dive headfirst into the world of entrepreneurship. Yup, you heard that right. We're talking about instilling that problem-solving mindset into every classroom. Why? Because our students aren't just facing equations and essays—they're gearing up to tackle real-world puzzles. Mastering algebra is important, but so is thinking like an entrepreneur. Students need to learn the art and skill of of spotting problems, finding creative solutions, and hustling hard to make things happen. And that's the secret sauce for thriving in an ever-changing world. “Back in my day…” is a notorious saying pervaded by the older generation to the young. It’s a right of passage to expect that elders believe their life is more challenging than that of their kids or grandkids.

However, in 2024, it prompts the question: How true is this in today’s world? It’s become increasingly clear that technological advancement continues to accelerate at an increasing pace, almost representing a mathematical LOG. The rapid development and implementation of artificial intelligence will only fuel the fire of progress. What does this mean for education? Even the most progressive institutions in education are finding themselves on the back foot when it comes to deploying technology in the classrooms. There doesn’t appear to be a grand strategy across the Western world regarding managing technology in schools. Some schools take an aggressive approach and ban all phones from K-12; others allow specific times to use the phones, while others offer 1:1 technology deployment in a more open approach. What is the correct solution? Nobody really knows. We’re living through a technological revolution that is unprecedented. We really have nothing to compare it to in the past, which makes the situation more difficult to manage. Perhaps there is something to the older generation’s standard quibble. Life may have been more difficult, but it was a little more predictable. How are you deploying technology in the classroom? Motivating young minds is like unlocking a treasure chest - complex, challenging, but oh so rewarding! The landscape of education is evolving, and so is the nature of motivation, especially when it comes to our students. For years, our schools have primarily relied on external motivators to inspire learning, with grades and external pressures driving the educational engine. Back then, this system seemed to work wonders. Students strove for top grades, propelled by the support and encouragement of teachers and parents, believing that academic success was the golden ticket to promising careers.

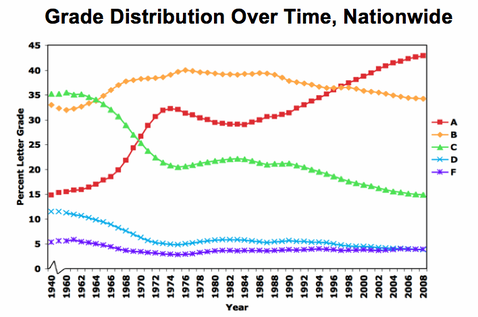

But fast forward to today, and the picture has changed. Grades, while still significant, are losing some of their magic. There's this growing pressure for every student to reach extraordinary heights, resulting in what's known as "grade inflation." The gap between weaker and stronger students narrows, even though average intelligence levels remain unchanged. Teachers, facing parental pressures, might feel compelled to inflate grades, possibly due to the increased investment of resources and expectations placed on fewer children within families. Enter "safetyism," a term coined by Jonathan Haidt, describing a trend where parents' increased involvement limits children's learning through fewer chances for trial and error. This protective environment might inadvertently diminish children's motivation at school, as the safety net seems always in place. The digital realm plays its role too. With the vast ocean of content available on platforms like YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram, school feels less enticing. These captivating bite-sized snippets chip away at attention spans, making extended focus a rarity. Educators now have the challenge of crafting engaging materials to captivate their audience amidst this sea of distractions. So, what's our game plan for today's education? It's about balancing external motivations like grades with nurturing internal passions for learning. Let's teach our students not just to study for the grades but to fall in love with learning itself. One exciting approach is through inquiry-based learning, where students take the reins of their learning journey. Imagine a unit exploring space through the lens of water, uncovering the intricate connections between water and life. They'd dive deep, employing technology to hunt for extraterrestrial water sources, sparking a lifelong love for exploration and discovery! 🚀🔍🌌 And for our younger learners, how about a thrilling inquiry-based project? Imagine delving into the secret lives of animals – researching their habitats, diets, and behaviors! Let them embrace their curiosity, sparking a journey of wonder and exploration. 🐾🔍✨ Education comes from the Latin educere, meaning ‘to draw out’ the pupil. Interestingly, the Latin word educare, meaning ‘to mold or train’ was also used in ancient times to describe education. Although both terms sound similar, they have very different meanings. Modern education has developed along the latter. In our current iteration of education, students are assumed to arrive at school each day with a little bit more empty space in their brains to fill with knowledge. It’s the teacher’s job to instill curriculum proficiency through rote learning. While most classrooms today aren’t the ‘drill and kill’ style where facts are repeated until committed to memory, even research projects follow a rote style where everyone produces a piece of work based on a specific set of requirements. This is a result of our increasingly outdated model of learning where we wish to produce students who can follow a recipe of instructions to obtain a specific skill set. This worked well from the birth of education to the 80s, when many jobs in western society were still industrial-based.

Now, in the throws of the service economy, we’re seeing a rapid departure from skill development in school to the skill requirements of modern jobs. It turns out that spending time learning facts and following specific project guidelines for 8 hours a day does not lend the creative skills demanded in today’s creative economy. Schools should drive to incorporate more educere in their curriculum. We should view education not as a way to deliver information and instruction in bite-sized peices but to help children develop as critical thinkers. How much of the work being produced in your classroom is recipe based? Can you design a lesson where the student has a chance to create their own learning? That’s educere in action! Life is not at all like the heroic Hollywood movies where the main character faces a setback and then musters the courage to overcome it and win the day triumphantly - all in a few hours. Real life has much more nuance to it. In many instances you often won't know that you're facing an obstacle and certainly may not recognize the path to a winnable solution. Countless studies have shown that humans are much more robust than previously thought and can handle and recover from utter catastrophe. On the other hand, we reliably and consistently overestimate obstacles and setbacks as impossible barriers to overcome.

This, of course, is a result of evolutionary pressures insuring that we don't take too many risks and when disaster does strike we've been gifted fortitude to carry on. It also has the ability to buffer us from permanent mental paralysis so we can recover from tragedy. Unfortunately, theses mechanisms work wonderfully in a primitive environment and not so well in the tech-focused world of modern times (see all of Twitter). One answer for living a productive modern life comes from the ancient wisdom of the stoic philosophers. They encourage you to follow the virtues of Wisdom, Justice, Courage and Moderation. Courage is an essential component of your legacy because unlike the movies, you may be asked to answer the call at an inopportune time that may be littered with easy exits. In those moments where you could stand-up for injustice, challenge the status-quo, do a thing that is impossible or run toward danger while others run away, you require the moral and sometimes physical courage. In modern times, it's easy to jump on a keyboard and speak out against an injustice. The problem is that it often begins and ends behind the keyboard without any effort to physically change something. We call this virtual signalling. It's the process of finding the minimal possible dosage to signal to others that you're with them or how you're a 'good person' without needing to prove it. The result is a system hack where we get the dopamine hit without the risks and rewards associated with actual work. This is not courageous. “To each,” Winston Churchill would say, “there comes in their lifetime a special moment when they are figuratively tapped on the shoulder and offered the chance to do a very special thing, unique to them and fitted to their talents. What a tragedy if that moment finds them unprepared or unqualified for that which could have been their finest hour.” Courage is answering that 'tap' on the shoulder. It calls you: To take a risk. To challenge the status quo. To run toward danger while others run away. To rise above your station. To do a thing that people tell you is impossible. Will you be ready to answer the call? Student success departments in K-12 education are some of the busiest places in a school. In the last two decades their workload has doubled and in many cases tripled.

"I can't keep up" as one high school guidance counsellor recently posted on Facebook. According to Johnathan Hiadt, rates of depression, anxiety and suicide among teens has skyrocketed since 2015. The numbers have steadily increased since the start of the COVID pandemic and show no signs of slowing down. Simon Sinek believes that over coddling has led to a dramatic decrease in teenagers and young adults abilities to solve problems effectively. Experiencing setbacks is a normal part of life, but when those setbacks are fixed for you as a youngster, you don't acquire the the skills needed to deal with them as an adult. Trees need the wind to grow strong. If trees aren't exposed to wind and weather, they will not expend the extra energy to reinforce the cells in the base and trunk. No problems means no need to invest in something that isn't there. When a tree grows without being exposed to wind, they will grow tall and wide. However, when a thunder storm arrives, they will be the first to fall. If there's one thing that is certain in life it's that storms will always eventually show up. Downshifting is the movement of slowing down. Not just physically, but in every aspect of your life including your work. Downshifters work less, consume less and stress less. The theory of the movement is founded in the belief that there's an ideal work-life balance that can be reached to maximize the greatest life satisfaction. It became popular in the mid 90s when the world was arguably at the most stable point in modern times. Crime was rapidly declining, the economy was booming and politics were boring. Many people recognized that working more didn't seem to provide the necessary glory it once did.

Downshifters believe that working beyond a certain threshold results in diminishing returns. This makes intuitive sense. We only have so much time in day and finding the correct balance between the opposing forces of work, family, friends and fun can be difficult to manage. Work 14 hours a day and you might be too tired to meet up with your friends on Friday after work. We've all been there. According to the downshifiting movement, the best way to find the correct work-life balance is to seek out the 'minimum effective dosage' of work you require to maintain your ideal lifestyle. How? Break out the math! If your salary was cut in half - along with your working hours - what financial obligations would you need to remove in order to keep your books on the positive side of your balance sheet? It may be less than you think! Secondly, since you'll have less money but more time, what will you do with it? European vacations and Caribbean cruises are generally not the ideal goals of downshifting. Instead downshifters choose to create. Write a book, code an app, paint a picture, build a shed. The key factor here is to make productive use of your time by creating. The creating doesn't have to be a solo endeavour. Maybe you volunteer at the hospital or in a classroom. Perhaps you train to become a local firefighter or community watch member. Be productive. With less. Although the economic crash of 2008 and the political strife that followed (and continues to this day) slowed the movement down to the point where downshifting communities couldn't afford to update their websites, pockets of individuals carried the movement on. Today, the COVID pandemic has injected a new spark into the idea of downshifting. When we were all forced to slow down, we realized how much we were missing. Many people forced to work from home have reported how surprised they were to see how much nature came through their backyards. As we inch ever closer back to normal, it's likely that we'll see a seismic shift in our work habits. Many people will choose to work less and create more. The challenge is to keep away from the corporate distractions like Netflix and Tik Tok. But that's for another post... During the early days of the Iraq and Afghanistan war, the British and US military realized that improvised explosive devices (IEDs) were going to be more that just a troublesome nuisance in their pursuit of military objectives.

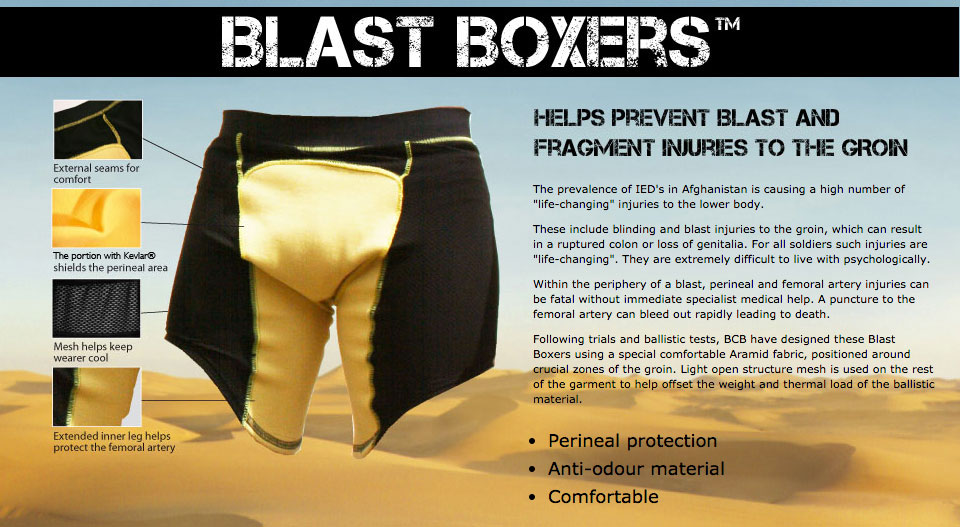

To counter the increasing number of casualties from IEDs - both individual and vehicle targeted - the US and British challenged their military innovation departments to develop equipment that could better protect soldiers on patrol. The result was an interesting smorgasbord of innovative ideas that were pitched to the military, ranging from specially designed IED resistant vehicles to Boeing's sci-fi Plasma Protection Field that would surround a vehicle during an IED explosion. One invention that fell under the radar (get it?) was bomb proof underwear, designed by the British military. The design came from the requests of soldiers on the ground who had first hand witness the destructive damage could cause to one's genitalia. The product ended up being a big bust for several reasons including cost to manufacture, lack of reusability (how do you wash them?) and the obvious fact that unless you build the underwear out of metal, nothing is really going to protect your junk. The last and most describing reason was that the under garment contained spandex and polyester which would melt and stick to the skin during an IED attack causing more damage than good (ouch). While it's almost impossible to predict the next innovative idea that will change the course of war (or your career), it is worth noting that a certain direction of thinking may assist in a greater chance of a positive outcome. Let me explain. Instead of pouring money into protecting soldiers during IED attacks, what if the military pivoted from the defensive to the offensive? What if they doubled down on the idea that IEDs - usually just rudimentary shells tied together with a simple circuit and controlled by a remote, timer or pressure plate - could be defeated by avoiding or destroying them before it's too late? Undoubtedly the US military has a division of research focused on these issues. The real question is: How much are they investing time and money into these more 'far fetched' solutions? We often get caught 'behind the ball' in our professional lives and that forces us into an innovative mindset that is always catching up. Sometimes the best solutions are the ones when we look above the fray. It can be difficult, but it's necessary to make large transformational change. Othwersie, you might end up with bomb-proof underwear. In ancient Greece, education formed a part of your identify. Even though formal education was only reserved for males, females and slaves would often take-up informal education through private tutors (if they could afford it) or simply show up to the public square and listen to debate.

The Greeks led by the great philosopher's strongly believed that the purpose of education was eudaemonia - human flourishing. To be eudaemonic, one has the capacity to take advantage of the opportunities provided by culture. At the heart of this is ability to pursue truth. If you were an artist or a poet, your prose would reflect the culture either by questioning or supporting it. The population supported this critical thinking style because they too were eudaemonic and seeking the truth to the big questions. This created a positive feedback loop where a culture of ideas propelled other better ideas to front made Greece - and specifically Athens - the legend that it is today. The enlightenment hijacked this old idea of truth seeking and powered by the new tool of science, launched western civilization into the modern era. We got to where we are because ideas were openly scrutinized until they conformed to objective reality (or a close to it as possible). Evidence is an essential when seeking the truth. How much truth is being told in your classroom? How many sides of an issue are you presenting to your class? How much uploading of information are you doing with your students? It doesn't matter if you are a pre-school teacher or a university professor. As educators we must be constantly evaluating our positions and ideas to ensure that our rhetoric is balanced and offers students an opportunity to question everything. Sisyphus was the founder of Corinth, who like most ancient Greek mythological characters, had a mischievous and deceitful side of him. He killed guests and travellers to his palace in order to consolidate his supreme power. This angered Zeus who attempted to punish him but Sisyphus outsmarted the God twice. As a punishment for his trickery, the God Hades made Sisyphus roll a huge boulder endlessly up a steep hill. When he reached the top, it would roll back down and he would do it all over again. For eternity.

The lesson: Be good and face no punishment in the afterlife. Sound like any religions you know? According to Albert Camus, the myth of Sisyphus and his endless pushing of the ball up a hill, is just a metaphor for life. Camus believed that our existence is a struggle between finding meaning in your life and the 'unreasonable silence' that the universe provides to answer the quest for meaning. The daily grind. We've all experienced it as adults. Feeling like you're stuck on the hamster wheel of life. You start your Monday's looking forward to Friday at 5. The day's are long and the weeks are fast as the saying goes. Camus - who lived in France during Nazi occupation - said that this way of existing in the world is wrong. Seeking meaning and pleasure during your free time while subjecting yourself to the powers that be during work will lead you to live like the lesson of the Sisyphus myth - be good and face no punishment. Instead, look at the job of pushing a ball up a hill endlessly as the most rewarding part of the struggle to live a good life. When you reach the top of the hill and accomplish your goal it's not over. Ever. You begin again with a new goal. Many people may just find it much easier to tow the line and avoid the headaches of reaching beyond their capacity for more. As you get older, you realize that accomplishing those life goals like writing a book or running a marathon required a lot less effort and bit more commitment than you realized. Embrace the process of pushing the ball up the hill. Sure, you could stop and look how much further you need to go, but it will only make you feel small and weak. The hill will never get flatter. If you focus on every moment of the struggle, you will be able to find love and goodness and the power of the universe in a moment of writer's block or a traffic jam or a cold, damp and dark 10k run. The University of Missouri conducted a study that found 94% of middle school teachers experience high levels of stress, which could contribute to negative outcomes for students. Researchers say that reducing the burden of teaching experienced by so many teachers is critical to improving student success — both academically and behaviourally.

Anyone who works in education is likely nodding their head in agreement with the study’s findings. Teaching today is synonymous with the modern struggle - a very rewarding career that comes at an extremely high cost. For those adults who grew up on social media, the modern struggle is a result of the external pressures of dealing with a firehose of information being beamed directly into our skulls. Naval Ravikant beautifully explains how the modern struggle has left adults alone to fight against the addictive powers of technology. Overstimulation has resulted in the decline of mental well being as we spend more time trying to navigate a world where the truth becomes increasingly murky. Was that Instagram influencers photos modified? Why does perusing other people's amazing lives on the internet make me feel so bad? I was interested in buying a car and now I’m being bombarded with car ads. How did this happen? Operating in a world rich in technology has split our being in two. One that exists as the internet views us and one where we exist in flesh and blood. Say something wrong on the internet and there’s a chance your flesh and being self will be obliterated. Show something awesome on the internet and we get a strong dopamine hit, but the value of it declines exponentially and we’re forced to repeat the process all with the hope that we’re not doing something incorrectly. What does this have to do with modern education? In its traditional form, education is nothing more than an artist’s blank canvas. A school is a place where similar aged children gather to train to become productive adults. Any experienced educator will tell you that to produce a flourishing adult, it requires making mistakes and at times, it can be extremely messy. Some mistakes that are required to grow can be huge. Failing a test can be devastating, but it shouldn’t be anxiety-inducing. Learning comes from experience which is born from error-correcting. The best leaders (past and present) all share a common tenant - they failed miserably at some point. Churchill’s disastrous WW1 raid in Turkey taught him that overly bold action without proper planning will end in disaster. The D-Day invasion of France was the largest most elaborately planned battle in human history. Churchill’s experience directly affected modern history. If he hadn’t made that mistake, perhaps we wouldn’t be living in the world as we know it. Failing a test today more devastating than ever to students. Pressure from parents to succeed is at an all-time high. This leads to fragile beings who are unwilling to take risks in order to avoid failure. Without mistakes and calculated risks, one cannot grow. Coupled to this idea is that parents are more involved in students’ education. Teachers are under enormous pressure to ensure that each student is performing at their utmost abilities at all times. When students make mistakes, finger-pointing is often directed at the teacher or school. The accountability of the student is at an all-time low. Throw in the extra demands placed on educators by the system - professional development, recess duties, mandatory coaching, etc - and the time and quality of actual teaching becomes shockingly eroded. The solution to this escalating problem? Faith. Faith in our children’s ability to overcome and achieve without massive direct intervention from parents, teachers, and society in general. Faith in our education system to provide the appropriate curriculum, professional educators and safe working environments needed to allow student growth and development. Faith that although it might seem counterintuitive, the world is indeed safer, more productive and favourable than it has ever been. Faith that whatever we do, or don’t do, our kids will still seek out their interests and pursue interesting adventures. Faith that in spite of every opportunity we feel like our children miss out on, they will find a way to make the world even better than we left it. A quality life embraces suffering. Part of doing anything meaningful in life requires sacrifice. Listen to this talk given to a K-12 student body on the importance of believing in suffering. This wonderful blog post from the School of Life (see below) talks about the problems with the technology-rich, instant-gratifying world we live in today. Steven Pinker believes that there is no better time to be alive and it’s really hard to disagree with him. People are living longer, they are healthier and have access to an abundance of resources that might seem like a fantasy to someone living just a few hundred years ago. Why is it then that our happiness hasn’t trended the same way as everything else? It turns out, unsurprisingly, that humans are complex creatures who cannot simply be won over with material possessions. The industrial revolution showed us early on that having the means of production and consumption rarely translate into immediate happiness for everyone. Factory workers felt exploited and resented the owners and managers for doing it even though they were making way more than on the farm. Things haven’t changed much since the industrial revolution. Most people still struggle with finding meaning in their jobs. Although we make more money and have more stuff, it just leads us to get more frustrated because WE SHOULD be happier, right? We have little to complain about and yet, here we are. To make matters worse, the internet now knows what you’re into and constantly reinforces your beliefs. It’s easy to get stuck in a loop seeing the things you believe constantly popping up on the screen. This is affectionately known as the Instagram effect (getting bombarded with pictures of beautiful people and places makes us feel ugly and boring). The answer to our modern problems might be found in the thinking of the ancient philosophers. Aristotle, Plato and the Stoics that followed them spent a large portion of their time thinking about Virtue (yes capital ‘V’ virtue) and the trouble with achieving it. The Stoics placed their bets with the virtues: Wisdom, Courage, Justice, and Self-Discipline. They believed that the way forward was through the self. Today it’s much easier to speak your mind with an attempt to change other people’s behaviours instead of blaming ourselves as the Stoics would suggest. Once you realize that you’re in control of your life (more than you realize), it becomes much easier to confront the challenges you face daily. Take time to write down your goals and your faults. Figure out what you can fix up in your life in the short term. Most importantly, make a concerted effort to be a little bit better than you were yesterday. The road to happiness isn’t through stuff - it’s through the management of yourself. Why the World is Broken For those of us lucky enough to live through the early 21st century, when unprecedented advancements in medicine, agriculture and technology have rendered many of the evils of the past obsolete, the question remains: why are we still so miserable? If, as the scientists and academics tell us, our present age is the best possible time to be alive, why do so many yearn to return to an imagined (and illusory) past, whilst others look ahead with horror at a chaotic and doom-laden future? Despite what the Panglossians* say, we are right to suspect that all is not right with the world. Along with its manifest benefits, modernity has created societal divisions and psychological strains that stem (ironically enough) from its leading, profoundly optimistic ideas: that life can be made perfect; that progress is inevitable; that everyone is equal and capable of greatness. When reality proves these false, the result is widespread rage, misery and a loss of hope. We should never seek to return to the conditions of the past, but we should try to reclaim some of its outlook - less hopeful, more fatalistic, but better suited to the vagaries of the present. |

Time to reinvent yourself!Jason WoodScience teacher, storyteller and workout freak. Inspiring kids to innovate. Be humble. Be brave. Get after it!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed