|

After reading Jonathan Haidt's latest book, The Anxious Generation, I was left wondering: Is it really this bad?

Having worked as an educator with elementary-aged students (K-8) for over 15 years, I paid close attention to Haidt's data, especially for ages 10-14. Throughout the book, I juxtaposed my experience with his findings to make sense of my day-to-day experiences as a middle school teacher. Often, data-driven books like *The Anxious Generation* highlight trends across demographics but fail to capture the nuances of daily life in the classroom. This is understandable; no author can account for every variable when proposing a hypothesis. Instead, we rely on large data sets to determine trends. The trends presented in the book are indeed disheartening. Teens and pre-teens, both male and female, are experiencing a mental health crisis. Haidt connects this trend to the rise of the social media generation, who now spend the majority of their lives on a device. So, what does this look like on the ground from a teacher's perspective? I've often suggested that the pandemic was a significant factor in the decline of Gen Z's mental and physical health. The uncertainty around the role of school in the early days of the pandemic created a chaotic environment, prompting questions with no clear answers. I remember pondering: What are the minimum requirements for online learning? Should it be asynchronous or synchronous? Should students be required to participate in some capacity? Do they need to have their cameras on? Should they be graded? Amid the chaos, norms for online learning were formed across Canada and the US. Younger students were taught synchronously in a traditional style, while older kids had opportunities to work asynchronously. There were problems with both, but we hoped that throwing enough spaghetti at the wall would at least stave off some of the learning loss. As expected, students with attentive parents, access to resources, and a reasonable sense of self-discipline soared above those missing one or more of these variables. Many students suffered alone, inevitably leading to an increase in anxiety and depression, much of which still affects them today. However, something happened during the pandemic that many educational leaders missed: Students learned that school was optional. The middle school students I taught during the pandemic checked out when forced to learn online. In some cases, I never heard from them at all, nor did they respond to emails. They never got punished for this. When deadlines came and went, I was not allowed to fail students. At the time, it seemed the right thing to do. However, as more assignment cycles passed without submissions, it started to stick. Students realized that school was optional. When things returned to normal, the vibe of school changed. Students seemed less motivated to participate in school and definitely less intrinsically motivated overall. It's hard to pin down the exact vibe, but it seemed that the wind had been taken out of their sails. It was almost as if they didn't know why they needed to be in school other than their parents making them. Along with the wave of indifference came a tsunami of identity crises that shook the foundations of school cohesion. Middle school students began identifying themselves in the third person, using they/them pronouns. Some went further to identify as the opposite sex. It wasn't just one or two; it was more than half in some classes. Just a mere two months prior, they had been wonderful, loving students with little support required. Now, they all seemed to have issues—anxiety, depression, ADHD—and were happy to tell you about it and even more excited to use it as a way to avoid actual school work. In times of rapid, drastic change, real leaders emerge. Unfortunately, in many cases, including mine, leadership embraced this new world with little critical thought about the long-term consequences. Students were allowed to hide their identities from their parents, meaning they could show up at school and change their name and gender, and teachers were not allowed to mention it outside the school walls. Students would come to school with what appeared to be cuts on their arms, and all I could do was hand the case to the leadership. The trap that school leadership fell into was directly connected to one of the great untruths from The Coddling of the American Mind: "Always trust your feelings." As Haidt and Lukianoff explain, ideas like "personal truth" and "lived experience" too often place feelings on the same level as facts. Feelings, of course, are subject to countless cognitive biases. Facts are facts because they're exempt from feeling. When we let young people, who are in the midst of puberty's emotional rollercoaster, believe their feelings are the truth, we end up with students identifying as different names and pronouns at school. A leadership team that supports this untruth creates a negative feedback loop where anything goes at any time because students feel like it should. As Katharine Birbalsingh suggests, students need tight guardrails because the world is a big, unknown place. Having boundaries allows them to explore within those boundaries while mitigating danger. This doesn't mean smothering them with rules; it means enforcing the rules to provide the 'safety' that students seek. Educators have let students' feelings drive their learning, resulting in a curriculum focused on student motivations rather than school goals. A great example is the reduction in the rigor of mathematical education. In California schools, algebra has been removed from the 8th-grade curriculum. In Ontario, 9th grade has become de-streamed (meaning no advanced classes). The goal wasn't to punish the smart but to help motivate the bottom-of-the-curve students who may "hit their stride" as they mature. It was thought that difficult math would turn students off the curriculum before they matured enough to "really get it." Unfortunately, there is no statistical evidence supporting this assumption. Jo Boaler, the Stanford math educator who led this charge, has recently come under fire for manipulating data on this very issue. Another important variable is social media. The Anxious Generation beautifully describes the overt effects of social media on kids' mental health, so I won't delve deeply into it. (As I write this, my 10-year-old is endlessly scrolling YouTube shorts on his tech time. More about this in another post.) However, there are downstream effects that the book doesn't explore enough. One significant change I've noticed over the years is groupthink. While the book mentions the susceptibility of females to groupthink, it is a larger issue than we imagine. Many middle school students will be captured by groupthink in an attempt to fit in. It has become increasingly ideological over the years. Pronoun usage is the most obvious example. Often, those students who use different pronouns do so as a cluster of friends rather than being the only one in a friend group to do so. In my experience, it's the students traditionally labeled as part of the outgroup. This makes intuitive sense—one way to differentiate yourself is to change your identity entirely. The speed and intensity of this change is directly influenced by social media. From my experience, there is a direct correlation between the amount of time someone spends online and the degree to which they echo a specific doctrine. Students who spend time on platforms like TikTok are driven by algorithms into feeds where their ideas are easily validated without criticism or critical thought. When these ideas are brought into school, teachers are forced to either validate, ignore, or push back. In our current educational environment, validation seems to be the only viable pathway. Ignoring is something I've practiced with the intention of protecting my job. Pushing back is the ultimate no-no and, in the one time I tried, landed me in a meeting with the head of the school. What can educators do to ensure students have an environment that both challenges their learning and makes them feel secure? One idea is to remove the focus on lived experience and instead focus on innovation. By innovation, I mean inspiring students to create concrete solutions to issues. For example, take history as it is, and instead of trying to rewrite it, have students focus on the innovations that made the world the place it is today. Slavery, or in Canada's case, the treatment of Indigenous people, is a hot topic in education. When teaching these issues, the focus is almost entirely on the disadvantages of the legacy of these systems. Teaching students that the legacy of the system is inherent today and is essentially stuck unless we make drastic 'equity' changes is not an effective means to change that system. Certainly, teaching the dark side of history shouldn't be ignored in education. However, it would be much more beneficial to students to show how changes were made to improve the lives of disadvantaged people. Britain outlawed the slave trade and used its powerful navy to enforce the rule against other sovereign nations. Without this action, slavery would have taken much longer to dissolve. In Canada, students should be taught the policies that were put in place to help support the Indigenous people to thrive. These include tax benefits, grants, and other government programs implemented federally to correct some of the misgivings. The students can then examine the success rate of these programs and develop strategies to continue to integrate marginalized individuals into society. The trouble with only showing the dark side of history is that it inevitably leads to activism in the form of protest. When students are taught that everything is systemic and cannot be changed, it often results in very binary thinking. Sure, this can be effective in some cases. However, it is such a common tactic now that its effectiveness has been greatly eroded. Blocking traffic in the name of climate action ends up losing public support, not gaining it. Teachers who promote this methodology would argue that 'awareness' of the issue is the ultimate goal. Unfortunately, the internet age has created an environment where we have theme days, weeks, months, and even *seasons* for all kinds of issues. We've over-saturated the attention market. But is it really that bad? The culture inside educational institutions has changed enough that it is increasingly difficult to challenge ideas constructively. The trouble I have experienced is related to the degree and intensity to which ideas and concepts are implemented. For example, our school raises the pride flag at the beginning of Pride Month in a school-wide ceremony. I objected to having students from K-6 attend this ceremony, citing that it is largely irrelevant to their stage of development and may cause confusion, especially if some of these issues haven't been discussed at home. The blowback I received from what I thought was a reasonable question was intense. The organizers of the event couldn't fathom why I would question anything about it and felt personally offended that I offered such a suggestion. This is the difference between five years ago and today. People are so entrenched in their beliefs that it is almost impossible to have a difficult conversation. The result is that these ideas do end up going too far. In one heinous example, a grade 9 student stood up at a school-wide ceremony during a sombre assembly reflecting on the Montreal Massacre and said she was scared to leave the house because white men were going to rape her. Instead of being reprimanded, she was celebrated as brave. The slippery slide into aggressive activism happens when we don't put up appropriate guardrails for students. Educators have created an environment where students' thoughts and feelings are paramount in the classroom. It is believed that unless kids feel safe, they will not learn. This would certainly be appropriate for the pre-internet generation, but in today's student body, who are chronically online, it doesn't work because they end up bringing their polarizing beliefs into the classroom without any challenge from the adults in the room. Educational leaders need to decide what exactly the purpose of school should be. What should the students look like when they graduate? What are the non-negotiable skills they should have? How will you know they have those skills? Once these questions are answered, you can work backward to find the classes, programs, and extracurriculars needed to produce high-functioning students who are prepared to enter the next phase of their educational or life journey. When you use this lens to view the purpose of education, you quickly realize that safetyism, pronoun usage, and critical social justice are not key initiatives for producing flourishing students. Educators often need reminding that we are not substitute parents and certainly don't hold the moral high ground over them. Challenge-based learning (CBL) is a powerful tool that enables students to tackle personal, local, or global challenges while gaining knowledge across various subjects like literacy, math, science, technology, and the arts. Its core aim is to motivate students by connecting their learning to real-world problems, making their educational journey more meaningful and impactful.

One of the fantastic aspects of CBL is its flexibility. Unlike other learning models such as project-based learning, CBL can be implemented in classrooms of any size and duration. Whether you have just a single lesson or an entire school year, CBL can be tailored to fit your needs. The ultimate goal is to help students apply their learning to develop essential job and life skills, empowering them to tackle even larger challenges in the future. CBL can be seamlessly integrated into almost any subject at any time. Let's explore its key phases: Engage, Investigate, and Act. Engage Big Ideas: These encompass topics that are significant to your class, community, or the world at large. For instance, themes like Climate Change, Social Media Impact, the Purpose of Education, Democracy, or Artificial Intelligence can serve as starting points. The goal here isn't to pinpoint a specific problem but to brainstorm overarching ideas that encapsulate numerous smaller concepts. This approach helps students understand the complexity of challenges and encourages them to think critically. For example, when exploring Climate Change, students can delve into subtopics like global warming, deforestation, or plastic pollution in oceans. Embracing big ideas fosters diverse perspectives, allowing room for exploration without the fear of a wrong answer. Essential Question: This narrows down the focus to a specific area that students can explore. Essential questions are framed to be reasonable, achievable, and realistic, often starting with "how" or "how might we." For instance, in the context of Climate Change, an essential question could be: "How can we reduce the amount of Carbon Dioxide in the air?" or "How might we minimize our school's carbon footprint?" It's crucial for essential questions to be open-ended, avoiding single-solution scenarios, which could indicate a narrow scope. Challenge: This connects the big idea and the essential question, serving as the driving force behind the learning process. Challenges should be broad and extend beyond individual or team boundaries. For example, if the essential question revolves around reducing the school's carbon footprint, the challenge could be "To promote a healthy environment." Depending on the context, students may opt for a more localized challenge, such as "To construct an environmentally friendly school." Investigate Guiding Questions: Once a challenge is identified, students embark on a journey of exploration. The cornerstone of this phase is questioning, as it lays the groundwork for further investigation. Educators play a vital role in guiding students to formulate insightful questions. Depending on students' age and skill level, teachers may scaffold questions or provide examples to enhance students' questioning skills. Using the essential question as a compass, students delve deeper into the issue, posing inquiries that drive their research. For instance, when addressing the question "How might we build an environmentally friendly school?" students might ask: "What defines an environmentally friendly school?" or "What steps can we take to improve our current environmental practices?" To facilitate this process, educators can employ various techniques, such as timed tasks where students generate questions independently and then collaborate to refine them. Additionally, leveraging shared documents like Google Slides or Jamboard allows for community or expert input, enriching the question generation process. Activities and Resources: This stage involves creating a roadmap for addressing essential questions. Students brainstorm tasks and activities aimed at answering these questions. For instance, when exploring the concept of an environmentally friendly school, activities could include researching existing eco-friendly schools, identifying accreditation bodies, or reaching out to relevant organizations for insights. Educators may need to provide additional support, especially for younger students, in aligning tasks with essential questions. However, as students progress, they gain independence in navigating research avenues. Synthesis: Here, students consolidate their research findings into a cohesive narrative. Visual tools like infographics or spreadsheets aid in presenting information effectively. This phase not only facilitates knowledge synthesis but also serves as the foundation for the final phase—Act. Act Solution: Armed with comprehensive research, students design innovative solutions to address the challenge at hand. It's essential to emphasize the importance of creating solutions that are novel, feasible, and impactful. While encouraging creativity, educators should steer students away from overly simplistic solutions and encourage deeper exploration. For instance, instead of a conventional poster campaign to reduce waste, students could design a pedal-powered generator to illustrate energy consumption. This approach integrates additional skills like design and engineering, enriching the learning experience. Implementation: Once solutions are finalized, students transition to implementing their ideas within the community. Whether it's showcasing their projects at school events or soliciting feedback from community members, this phase emphasizes real-world application. Research indicates that students who teach others about their projects retain information better, highlighting the importance of effective communication and dissemination of solutions. Evaluation: The final step involves reflecting on the entire process. Students assess their journey, identifying areas for improvement and celebrating successes. Reflection can take various forms, including written journals, feedback forms, or video reflections. Additionally, articulating the CBL process reinforces learning, ensuring students internalize the value of each phase. The bottom line Challenge-Based Learning equips students with the skills and mindset needed to tackle complex real-world challenges. By fostering inquiry, innovation, and collaboration, CBL transcends traditional learning boundaries, empowering students to become active agents of change. Let's embrace the power of CBL in our classrooms and nurture the next generation of problem solvers and innovators! Kenyan Eliud Kipchoge set a new world record for men of 2:01:39 on September 16, 2018, at the 2018 Berlin Marathon. It is the closest a human has come to breaking the much sought after sub-2-hour marathon. Much like Roger Bannister’s ‘miracle mile’, most sports scientists believe that it is within human capacity to break this mark at some point.

It hasn’t always been this way, check out what happened in the marathon at the 1904 Olympics in St. Louis: The first place finisher did most of the race in a car. He had intended to drop out, and got a car back to the stadium to get his change of clothes, and just kind of started jogging when he heard the fanfare. The second place finisher was carried across the finish line, legs technically twitching, by his trainers. They had been refusing him water, and giving him a mixture of Brandy and Rat Poison for the entire race. Doping wasn't illegal yet (and this was a terrible attempt at it), so he got the gold when the First guy was revealed. Third finisher was unremarkable, somehow. Fourth finisher was a Cuban Mailman, who had raised the funds to attend the olympics by running non-stop around his entire country. He landed in New Orleans, and promptly lost all of the travelling money on a riverboat casino. He ran the race in dress shoes and long trousers (cut off at the knee by a fellow competitor with a knife). He probably would have come in first (well, second, behind the car) had it not been for the hour nap he took on the side of the track after eating rotten apples he found on the side of the race. 9th and 12th finishers were from South Africa, and ran barefoot. South Africa didn't actually send a delegation - these were students who just happened to be in town and thought it sounded fun. 9th was chased a mile off course by angry dogs. Note: These are the first Africans to compete in any modern Olympic event. Half the participants had never raced competitively before. Some died. St. Louis only had one water stop on the entire run. This, coupled with the dusty road, and exacerbated by the cars kicking up dust, lead to the above fatalities. And yet, somehow, Rat Poison guy survived to get the Gold. The Russian delegation arrived a week late, because they were still using the Julian calendar... in 1904. In just over 100 years we have gone from drinking rat poison during a run to now pushing the limits of the human body. What happened? The obvious answers are correct - the birth and development of sports science, the invention of proper clothing and the increase in the number of people participating in the sport. The more underrated answer is the development of the human spirit. It’s true that we’ve been able to survive much tougher conditions throughout our history. However, we’ve needed to rely on mythical stories or hearsay evidence to motivate us to push through our limits. After Bannister broke the 4 min mile, only one other person managed to do it (John Landy) within a year. However, within 25 years hundreds of people had broken the 4 min mile and even today a strong high school runner can do it. Knowing that it was possible made a big difference. It’s much easier to chase down dreams when people you can relate to having accomplished them. As our world becomes increasingly specialized, we’ll see these kinds of records continue to be broken. Most youth athletes spend a vast majority of their extracurricular activities on just one sport. There is a danger, however, in embarking on such a journey. What are you missing out on by sacrificing it all for one sport/opportunity/dream? It’s important to expose yourself to a wide variety of experiences before making the leap to specialize. Once you decide, definitely put all your eggs in one basket. Find someone who you can emulate - even if they’re physically inaccessible. And then get after it! Records are obstacles to be broken! Do you practice surgery in your spare time? Probably not. To become a surgeon you need years of education and hours of practice. It makes sense that there are fewer surgeons in the world than baristas. When you require surgery you probably don’t ask the doctor for work samples or to speak with one of his former patients. You trust him because he’s earned it.

The same is probably true of the lawyer you hire. She’s a professional who has worked hard to get to the top of her firm. No need to go through a tender process. Trust is easy to establish because she’s a certified professional. The trouble is that for most of the jobs out there, professional certifications don’t require years of specialization. A teacher for example only requires a 3-year university degree and one year of college. Other jobs require almost no certification. Being a teacher, social media influencer, YouTube personality, website designer, and programmer are easy to do because there are very low barriers of entry. Many people feel like they’re at least somewhat capable of being successful at these jobs. This causes a big competition for those who are really trying to make a career out of it. With big competition comes less trust. As a customer, you have to be a little cautious hiring a photographer for your wedding because anyone with an iPhone can (rightly) claim to be a professional. To make things worse, automation and educational inflation are combining to erode the number of employment opportunities for university and college graduates. According to Gwynne Dyer’s latest book, by 2050 the unemployment rate could be as high as 40%. Jobs for highly specialized are becoming increasingly more competitive as education becomes more accessible. Getting a job as a doctor often meant just surviving medical school. With more and more students enduring the medical field, it is increasingly becoming more important to finish at the top of your class in order to separate yourself from the pact. If you don’t want to specialize, are you doomed? Not likely. Being able to separate yourself from the pack has always been a valuable skill. Now it’s essential. In Seth Godin’s book The Dip, he describes the process of becoming an expert as surviving ’the dip’. It’s that point where most people give up because it gets too expensive, it gets harder, or they lose interest. If you can focus on photography, get the correct equipment and simply outlast the others in the field you’ll be successful. The challenge is that the more people who are in the race, the more likely it is that some may also overcome the dip. Choose something you love, understand the difficulties of being successful at it and fight through the dip. Good luck! The NY Times recently wrote about the importance of being bored, especially for children. The most prolific line in the article mentions the endless battle of children and parents vs boredom.

"Nowadays, subjecting a child to such inactivity is viewed as a dereliction of parental duty." Our children today are viewed as an investment and one that is expected to deliver exponential returns. The more activities we put kids in, the more likely they’ll grow the skill set to be change makers in the world. The great paradox in this all is that when asked what they want to be when they grow up, most kids want to be famous or an assistant to someone famous. It seems as if all these extra circular activities aren’t as effective as we thought. On top of that, the massive scheduling of young people has lead to a rise in an inability to manage time properly (since it’s being organized for them) and solve problems. Even worse, many kids struggle with boredom. Their inability to make-up games in an unstructured environment greatly caps their creative potential. All of the great minds of history shared one thing in common - the ability to see something that wasn’t there before. These profound ideas were generated in an atmosphere of what would today be called “absolutely boring”. Einstein developed the theory of relativity as a patent clerk - literally one of the most boring jobs one could undertake at the time. The boredom allowed his brain to work on other meandering details that included nothing less than the absolute transformation of our view of the universe. Will boring our kids lead them to develop the next best explanation of dark matter? Unlikely, but we cannot discount the opportunity of creative thought that border brings. Design thinking will get your idea out quickly and efficiently. It will not, however, give you a fundamental paradigm shift. That comes with quiet thinking in a bored state. Social media has fundamentally changed the way we communicate. It’s now easier, faster and far more efficient to send a text message, tweet or snap to interact with your colleagues, friends, and family.

The speed of modern communication has come at a cost. Misinterpretation, peacocking (making it seem that things are better than they are), and virtue singling have replaced the ability to engage in meaningful conversations. Now online conversation is mostly one-way and takes place with less than 400 characters. Any counterpoint can be met with ignorance, indifference or hostility. Civil discourse among individuals is on the decline. It should therefore be no surprise that social media is now becoming weaponized. With little opportunity for explanations, conversations and respectable debate on tough issues such as sexism, racism, and gender identity, huge divides have erupted in the population. It seems to be common sense is now off the table during debate and individuals who have experience with some of these intense issues need to pick a side and stand firm. While social media can’t take the entire blame for this hostile environment we’ve created for ourselves, it is responsible for how we are conducting our less than efficient means of communicating with one another. Tough issues are tough because there’s no easy solution. Simplifying the arguments of these topics only appeals to our primal side. We have evolved over thousands of years to be able to listen to one another and take feedback. When you eliminate this ability you push civilization in the wrong way. Perhaps (and likely) we’ll be just fine and figure it out. In the meantime, suspending judgment on every micro issue is probably the best course of action. Gillette recently released a commercial that has now become infamous. Proctor and Gamble have undoubtedly thrown their hat into the political ring and the results so far have been disastrous (just look at the dislikes). The commercial’s message is a good one - treat each other with respect (especially men) - however, it’s the timing that is all wrong.

The world is currently in the middle of a culture war. Hierarchy's everywhere are under attack and with the weaponization of social media, anyone with privilege or power needs to watch their back, regardless of their track record. One battle being fought tooth and nail in this broader culture war is the dismantling of ‘toxic masculinity’. The proponents of the elimination of toxic masculinity argue that men are hardwired to behave inappropriately. Those who men who manage to respect other males and treat females properly are a rare and dying breed. Gillette (under P&G) decided to draw a line in the sand, essentially assuming that the feel-good message would resonate with their customers. Boy, did it backfire. Why? Feel good marketing is nothing new to P&G. They’re one of the pioneers in the advertising space. The trouble with this particular Gillette commercial is that it managed to throw fire on an already raging blaze of conflict between men and essentially what is shaping up to be the far-left establishment. When corporations take political and moral stances, they must be very careful not to alienate their target market. Most consumers know that the sole purpose of a corporation is to make a profit. This agenda becomes abundantly clear when corporations begin to virtual signal. What they’re really saying to us is “hey, look at us, we’re the good company who is standing up for your beliefs. We want you to buy our product because we care.” Plenty of market research shows that men who buy shaving products aren’t typically brand-loyal. They’re far more sensitive to price. The goal of all advertising is awareness and the message becomes almost secondary. This is proven every time you click on a link that starts with ‘This one simple hack…’ Surely, Gillette won’t crumble with one unpopular commercial. Like most events these days, it will be soon lost in the sea of information. There is, however, a great lesson on marketing to be learned! Most people feel like suffering is worth it because there’s a goal to be achieved. Weight loss is a great example. People starve themselves, eat strange foods and exercise to lose weight. The trouble is when they lose the weight and stop exercising and eating strange foods, the weight comes back. There is no end. Instead, you need to eat properly and exercise regularly (forever) to maintain a healthy body and mind.

Education falls into the same category. Study hard for the math test so you can get a good grade. Beware, there’s another math test around the corner. Of course, the tests end when you graduate to the working world, but they don’t really because the tests are replaced with the constant need to re-educate yourself. There is no end. Then why not embrace the struggle? Playing whack-a-mole with life's problems is exhausting, especially when there is no end. The interesting thing about suffering is that the more you embrace it the better you get at taking on more suffering. Real growth happens when you live in the suffering not when you live through it. Next time you’re taking on a problem with the goal of stamping it out, remember: There is no end. Students are taking to social media in droves to protest mandatory in-class presentations. Citing discrimination, they’re calling for alternatives to public speaking, especially for those individuals with anxiety.

Should public speaking be abolished from education? According to a recent article in the Atlantic, over 90% of hiring managers say that oral communication is an essential skill in the business world. Educators feel that public speaking builds confidence, improves critical thinking, and teaches debating skills. Traditionally, public speaking has been feared more than death. High school students are especially susceptible to presentation anxiety because it often takes place in front of their peers during a vulnerable time in their lives. A presentation that goes sideways could cause intense fear and anxiety. Is this good or bad? If public education’s main job is to prepare student’s for the world, then it would make perfect sense to continue to have kids practice public speaking throughout their schooling. Educational institutions are designed to be places of practice and learning that are sheltered from the harsh realities of the ‘real world’. If students can’t face their fears in this protected environment it's highly unlikely they’ll be able to manage a presentation in a business setting. Safeyism (the idea that we’re over protecting our children) and anxiety are very real problems in education today. It’s unfortunate that they happen to be polar opposites. Perhaps a hybrid approach to public speaking is the most effective way to keep it in schools (having kids present in smaller groups first is an example). In a world where populism is favoured over expertise, it would be a disaster to abandon our ability to converse using oral communication. Seth’s blog today talks about the importance of doing in the effort of learning something. This is a fundamental principal that sometimes gets confused when we’re in pursuit of a new goal.

So many of us can watch some YouTube videos and have the confidence to be the next president or knowledge to understand the dynamics of a complex economic and political system. The trouble is that experience is still the king when it comes to learning. You can’t swim by reading books or watching videos. Even advanced scientific theories have no credibility without experimental evidence backing them up. How many of you are teaching innovation without experimentation in your classes? Never under estimate the educational value of turning over a log to learn about habitats or programming a Sphero to reinforce computational thinking. ...is to understand that your job or career or goal requires you to keep showing up regardless of how you feel. Putting in your best effort each and every day will build the grit required to to great work. There must have been days when Michelangelo wasn’t jazzed about chipping away marble for hours at a time. He did it though and now we have David.

If you find yourself making the type of excuses that prevent you from showing up, then you may need to rethink your job or career or goal. In 1955 the average child spent 2-3 hours outdoors every day. Rain and snow forced some inside down into the basements of friends to build forts, play board games and generally horse around. When outside, kids made tree houses, played war games, hung upside down on monkey bars and rolled through the streets on their bicycles. This was all without parental supervision.

In 2018, the time kids play outdoors without supervision has shrunk to almost zero. Those kids who are granted freedom, typically have tight restrictions on where they can go and generally come from homes with single parents who work. Time in school and homework has increased exponentially as well. Homework is assigned in kindergarten and increases steadily until high school. Kids are now spending more time in structured play. Sports, music, art, dance and play dates are all organized, supervised and facilitated by adults. What are the benefits and consequences of a reduction in free play? First the good. Childhood injury and accidental mortality are at an all-time low. Supervising adults are able to intervene in risky behaviour early enough to prevent minor and serious injuries. Kids are becoming highly specialized at an increasingly younger age. Most NHL players being drafted now played only hockey growing up and did it throughout the entire year. The result is an NHL that contains a historically high level of skill, speed, and size. The same can be applied for almost all professional sports. Adult-child relationships are the strongest in recorded history. Kids now see adults as partners, leaders, and coaches instead of authority figures. Increased corporation between adults and children has led to more supportive and productive households. Teenagers are confiding their problems to their parents which allows for early interventions. Unfortunately, all of these benefits do come at a cost. Diagnosis of childhood anxiety and depression are the highest they have ever been. The attempted suicide rate for children and teens has more than quadrupled since 1955. Young adults ability to cope with setbacks in life has caused a monumental shift in culture at post-secondary institutions. Onsite school therapists are overwhelmed with students seeking support. Some statistics show that over 50% of all university students are diagnosed with either anxiety or depression at some point in their schooling. The course curriculum has changed to offer ‘trigger warnings’ for sensitive content that may potentially upset some students. In the younger grades, children are increasingly requiring adult intervention to solve interpersonal problems and structure their day. When offered unstructured time in school to solve a problem or create something new, students constantly require feedback and details for the outcome (ex. How do I get an ‘A’?). The message to push through the tough times and use ‘grit’ has mostly fallen on deaf ears because educators are increasingly finding it difficult to find the balance between safety and uncomfortableness in their classrooms. Living increasingly structured lives has reduced the ability for kids to learn appropriate self-initiative skills that can be found when setting up a game or solving a problem amongst themselves on the playground. It appears that Steven Pinker was absolutely correct when he tells us in his book ‘Better Angels of Our Nature’ that the world is safer, healthier and smarter. It’s impossible to predict what the future holds for a generation of kids who don't get to play very often. However, it does seem to be an important step in development for children (and adults). What is the difference between a leader and a manager?

Are the titles interchangeable? Traditionally, managers were the people who kept the systems running. They made sure the work was done on time and with the best quality possible. Managers trained, supported and praised workers to ensure that the widget was built correctly. You earned a management title when you had enough experience and intelligence to effectively keep the systems running. Leaders were visionaries. They took risks and led from the front. Leaders didn’t necessarily have to be the person at the top of the hierarchy. It was awarded to anyone willing to inspire others to follow them into potentially dangerous situations with the hope of coming out better on the other side. Sometimes in education, we get the titles mixed up. We tell students to be leaders but really we want them to be managers. Great managers get the student council running properly, they keep track of all their school work and submit it on time with their best effort, and they support their peers so that the whole system works better. Leaders push the boundaries of their education. They look for alternative ways to solve problems, they write controversial essays, and they seek out new ways to improve their school. They take risks and own up to their failures. They push for change. When you’re evaluating someone’s leadership abilities, make sure you’re not mistaking them for a manager. The original definition of trauma included only physical damage to a human being. Blunt force trauma was the result of an injury due to a motor vehicle accident or other non- penetrating wound suffered by an individual. That word has evolved over the years to include mental damage. The most famous being PTSD - post-traumatic stress disorder.

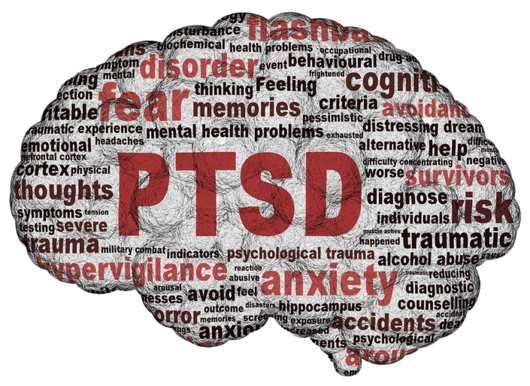

PTSD occurs when a person is exposed to a highly stressful situation such as a war zone or a natural disaster. People diagnosed with this condition find themselves locked into a highly altered state and are generally unable to disconnect from their experience even though the threat has been removed. In the old days of WW1 and WW2, it was called shell shock. PTSD is a very important adaptation for human beings. Evolution carefully crafted this condition in us back during a time where the world was ripe with danger. PTSD allows humans to maintain a highly alert state which clearly would have positive survival benefits if you had just witnessed a saber-tooth tiger attack your tribe. Today soldiers in war zones and EMS workers are the most likely to experience a diagnosis of PTSD. What is interesting is that when help is received, there’s over a 90% chance of recovery. Humans are resilient. If our mental recovery from very traumatic events is possible, why is that we spend some much time and effort ensuring that children are shielded from events that may trigger negative emotions? Failure and criticism are non-existent in elementary education and quickly fading in high-school and university. It’s clear that teaching resilience and grit requires students to embrace pressure and possibly failure. Individuals who recover from PTSD often report living happier lives than before the traumatic incident. Recognizing that life is fragile, taking pleasure in the small things, and focusing on interpersonal relationships are the main reasons why PTSD patients are happier. Humans have complex stress systems built into our anatomy. We’re designed to be stressed and recover. Look at someone who lies in bed all day. Their physical bodies begin to atrophy. The only way to maintain a healthy body is to put it under some form of physical stress. Our minds are no different. Joint Task Force 2 (JTF2) is Canada’s version of the Navy Seals. They’re elite military operators whose skill sets range from training locals in the art of insurgent warfare to jumping out of planes behind enemy lines. They can fight in the desert, the arctic and under water. Unlike America’s special forces who can field highly specialized Navy Seals, Army Rangers, Green Berets, and Airforce Combat Controllers, the JTF2 are Canada’s only special force and need to be able to fight on land, sea and in the air, alone. Essentially, they’re the jack-of-all trades and they’re really good at what they do.

The challenge with being a one stop shop for national defence is that you can’t be an expert in everything. If you spend too much time training for underwater operations than you’re bound to miss out on important training for air insertion. So how does JTF2 train to be an effective fighting unit that is coherent in all areas of the battle space without being an expert in every area? Instead of being the best in one area, they learn to be really good in all areas. More importantly, they practice extreme flexibility. When they enter into dangerous combat zones, they’re acutely aware that they’re not experts in everything. They work together to minimize the risk and maximize success knowing that their skills may not be perfectly polished. This happens though detailed planning, having access to the best equipment possible and the understanding that failing to use their strengths is worse than overestimating their weaknesses. Extreme flexibility is a differentiating asset in a world where specialization is the norm. Kids are taught to be the best at a sport, a subject in school or an art. Nobody today is willing to settle for above average. The issue is that being above average at sports, school AND arts makes you far more versatile in a world of change than someone who has placed all their eggs in one basket. Understanding your strengths and embracing your weaknesses gives you the needed insight to perform in areas of unknown. The JTF2 prepare as best as possible but know that their strength lies in extreme flexibility. The next time you have the opportunity to participate in something you’re not an expert in, dive in guns blazing and embrace your weaknesses. It will only serve to make you extremely flexible. The purpose of education is to prepare an individual to reach their highest potential – to flourish. One characteristic of this philosophy is the idea that the student should be capable of independence. Individual autonomy promotes the critical capacity to make good decisions, independent of the beliefs of a group or religion. Home schooling may cover the curriculum of a pragmatist philosophy on education, but does it truly create individual autonomy independent of any religious or social biases?

Children who are educated in the home or in small groups under a religious doctrine (ex. Amish) are at greater risk of misrepresenting their view of autonomy. A student who is home schooled by their parents may receive a high-quality education similar to that set out by the state. However, a large portion of their education in social interaction may go unlearned. This subtle, yet extremely important, piece of the education puzzle could have severe repercussions for a home schooled student later in life. In On Education, Brighouse argues that true autonomy involves the ability to determine one’s own values. In home schooled situations, values may be imposed directly, or indirectly, limiting a child’s ability to decide their own views. For example, an Amish child may grow up to misrepresent modern social values as ‘evil’ or ‘ungodly’ simply because they had Amish values imposed on them from an early age. High attrition rates by young Amish are a great example of what can result when autonomy is not a primary focus of education. As an educator it is important to understand that a single-focused education in any area of schooling can lead to the development of homogeneous beliefs. It isn’t a teacher’s job to expose children to every possible religious or educational view. However, it is necessary to guide students to understand that the concept of choice is essential in the idea of individual autonomy. Teachers must promote critical thinking skills in all aspects of school. It is also essential to promote social interaction among students so that individual views and experiences can be shared. The idea that thinking critically about their own beliefs while taking into account the views of others, is essential in developing autonomy. A home schooled student would not have the luxury of social interaction with various view points and could disagree with or oppress other peoples viewpoints in social interaction. The philosopher Daniel Dennett argues that in the case of religion, children should be taught the history and beliefs of all religions. Then they should be allowed to make decisions without the influence of parents, teachers or religious leaders. In his book, Breaking the Spell, Dennett states that religious indoctrination can poison all of society. Although his thesis is religiously based, it certainly applies to the concept of schooling and autonomy. Children should be allowed to explore many different belief systems, viewpoints and religions and be given the ability to decide a value system for themselves. This is an ideal theory and difficult to represent in the real world because almost certainly everyone will be influenced by someone and in the case of children, they receive the strongest influence from their parents. However, the idea that a teacher can foster children to witness different viewpoints is essential in the development of autonomy. Home schooling is a moral issue that deals with a student’s ability to function as an autonomous member of society. Although publicly schooled and home schooled students may share the same skill set, the home schooled child may lag in social maturity. This social education is a key element to become truly autonomous. Without it, a student my not be able to flourish. For those who are a fan of the classics, you know that education has its foundation in both Plato and Aristotle’s philosophies on well being. Plato's famous cave analogy tells us that real learning occurs when we open our minds and assume that what we see, hear, feel and believe are just shadows. The mind can grow through the investigation of ideas by peeling back the dark vale that covers them. A modern view of this philosophy can be found in Steven Pinker’s book - The Blank Slate. He uses a science-based approach to contend that we’re all born hard-wired with plenty of knowledge. Much of this knowledge comes to the foreground when we mix it with experience. A great example is the acquisition of language. It appears that we’re born with the ability to communicate already mapped on our brains. Once we’re exposed to language, we seem to be able to fill in multiple gaps quickly. Our ability to infer seems to have been pre-installed at birth.

Aristotle believed that we learned best by interacting with knowledge. Our minds are empty vessels that can be filled to the brim with new ideas. Essentially anyone can learn anything as long as their brain is open and ready to save the knowledge. The traditional industrial style classroom leaned more on the Aristotle approach with it’s desks in rows and reinforcement of mathematical facts. Obedience was the key to learning. Follow the instructions and you will acquire the knowledge required to live a well-balanced for fulfilling life. In today’s classroom you’ll find a far more Platonic approach to education. The inquiry method of teaching is nothing more than Plato’s theory put into action. It’s interesting to note that only a brief moment of teacher education is dedicated philosophical education, and in the classroom almost nobody talks about either Plato or Socrates when asked about their teaching pedagogy. Why? Other than the risk of sounding archaic, many educators are likely unaware that they’re facilitating in this ancient theory of teaching. Instead they can confidently articulate their educational approach by reciting important terms such as ‘personalization, flipped-classroom, deep learning, wellness’ and many others. It is possible for a teacher to speak a sentence with so much educational jargon, even a Rhodes scholar might be confused. “By flipping my classroom, I’ve been able to take a personalized approach to teaching thus enabling my students to engage in deep learning with a growth mindset.” While this certainly sounds impressive, it’s covering up the core principals that both Plato and Aristotle preached about many years ago. The goal of education at any level should be to improve eudaemonia - the idea of human flourishing. In an educational setting, the tactics of achieving this goal (see the post below) are not as relevant as the strategy of developing competent, capable and critical thinkers. Whether you’re using personalized learning, flipped classrooms or have a focus on wellness, the goal is to either fill the students head with new information or expose her to new ideas that will allow her to learn independently. As a supplement to a blog post below, I have created slidecast that was given to the senior school . In the talk, you'll learn why fear and failure are keeping you from aiming high and being a better person. Podcast version available here. Enjoy! Daedalus had been imprisoned by King Minos of Crete within the walls of his own invention, the Labyrinth. But the great craftsman's genius would not suffer captivity. He made two pairs of wings by adhering feathers to a wooden frame with wax. Giving one pair to his son, he cautioned him that flying too near the sun would cause the wax to melt. But Icarus became ecstatic with the ability to fly and forgot his father's warning. The feathers came loose and Icarus plunged to his death in the sea. What’s the lesson here? Don’t disobey the leader. Listen to what your parents say. Don’t try to imagine that you’re better than you are. Fall into the box that society puts you in. Don’t dream big. I think that’s dead wrong. It’s interesting to note that in the modern version of the story, the part about flying too low has been purposely left out. Seth Godin believes it was a result of the industrialization of education and need for competent workers. What happens if you fly too high? You get burned. You fail. You get embarrassed. When teachers are asked wha the biggest thing wrong with education today, do you know what that almost all of them say? We’re not teaching students to fail properly. Note the word properly. Is there a proper way to fail? That’s what we’re going to look at right now. The goal of every educator should be to have students walk out of the class each day with the knowledge of what it means to fail. Knowing this allows them to aim high. Would Icarus would still fly close to the sun if given a second chance? Yes! Why? Because, well, you already know. Who wants to live a boring, play by the rules life? Just check out your snaps, Instagram and other social media feeds. NOBODY puts anything online about an average day. Here I am, eating lunch or studying. People have the natural desire to showcase themselves flying high. What they don't show is the failure. That's arguable the most important part. Easter Island is the true story that Dr. Suess might have based the book 'The Lorax' on. It was home to a successful community for many generations. Over time, the limited resources on this isolated island began to disappear until one day, 'chop!' the last tree went down. Jared Diamond makes the story real in his brilliant article and book (thanks Seth Godin for linking this!). The question we could ask is: Who were the people that warned everyone about the pending crisis? Someone must have known about the potential danger, right? It's possible that the entire community was suffering from co-pilot syndrome. It's the condition where the co-pilot doesn't mention any potential danger to the flight crew because he or she feels that speaking up might disrupt the deeply taught culture of chain of command. Experienced pilots never make mistakes, especially obvious ones. Speaking up against them could get you in big trouble. So the co-pilot says nothing and the result can be disastrous. Perhaps the community on Easter Island was based on this premise. Of course the leaders have a plan for the disappearing resources. Speaking out against the plan could get you banished and that's not a good place to be on an isolated Island in crisis. Where in our culture do you see this type of behaviour? Do you feel comfortable speaking up in a meeting if you're on of the junior team members? Do you automatically assume that experienced leaders will always have it right? It sounds silly to think that way, but watch out, you might already be doing it. With a massive environmental catastrophe on the horizon, we can't wait to act. We need to speak up now. |

Time to reinvent yourself!Jason WoodScience teacher, storyteller and workout freak. Inspiring kids to innovate. Be humble. Be brave. Get after it!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed